Spontaneous order and Mensa

Column from the Mensa World Journal October 2013

As I type these words, I am catching my breath after an intense and stimulating four days in Bratislava, where Mensa Slovakia pulled off a spectacular EMAG, with close to 350 participants from many countries. Lectures, tours, games, food and music, all in good and intelligent company. The countdown for the seventh European gathering next year, in the Swiss city of Zürich, has now begun. The first meeting of the new international executive committee was held in conjunction, and we had several fruitful discussions. And a lot of hot air. Literally; a delightful heat wave warmed that charming old central European capital at the time. As I watched new ideas emerge out of all the inspired interchange, it occurred to me that I was watching spontaneous order in action. As this goes to the very heart of intelligence, I chose to dedicate my column to this topic. Allow me to explain.

Spontaneous order emerges from the bottom-up, in complex systems where each component has some degree of independent freedom. It is a simple fact of nature and such order can be seen everywhere, in ecology, in technology and most certainly in human culture. Nature is full of spontaneous order. Water molecules are never ”aware” how their respective movements in an atmospheric freezing process leads to the emergent symmetry of the snow flakes, and yet there they are. Without a central intelligence, an ant colony can still express more intelligence than each ant acting alone.

Human intelligence itself can be seen as a phenomenon that emerges from the interaction of billions of independent neurons collaborating in a spontaneous order. In a spontaneous order, intelligence is not so much the property of each single component, but rather something that appears ”between” all parts, making the whole bigger than merely the sum. This is true for individual brains, but all the more so for groups of people acting together.

Society is a spontaneous order, both in its universal meaning as the community of which each citizen is a part, and in the more limited sense, as in the high IQ society of Mensa. Anyone may have a vision of what society should be, and dream of the road to get there, but at the end of the day, there is simply no way that a master plan can be imposed top-down, detailing everything. For the devil is in those details, flapping storm-starting butterfly wings when nobody is looking, and so great plans are turned to nothing.

Creatures of evolution as we are, we would not be here if it were not for the emergent orders that arise spontaneously out of the chaos. Life itself exhibits several such properties, but in the pop literature about chaos and spontaneity, it is easy to get the impression that there is something inherently ”good” about them. Spontaneous order is neither good or bad, it just is, but wise leaders must remember to account for it. From any given perspective, some emergent orders are harmful, others are useful, and we can only tell afterwards. We can start by putting the chess pieces where we want them, but then the players will shuffle them around; out of simple game rules, complex strategies will emerge, culminating in that intangible thing that makes chess worth playing.

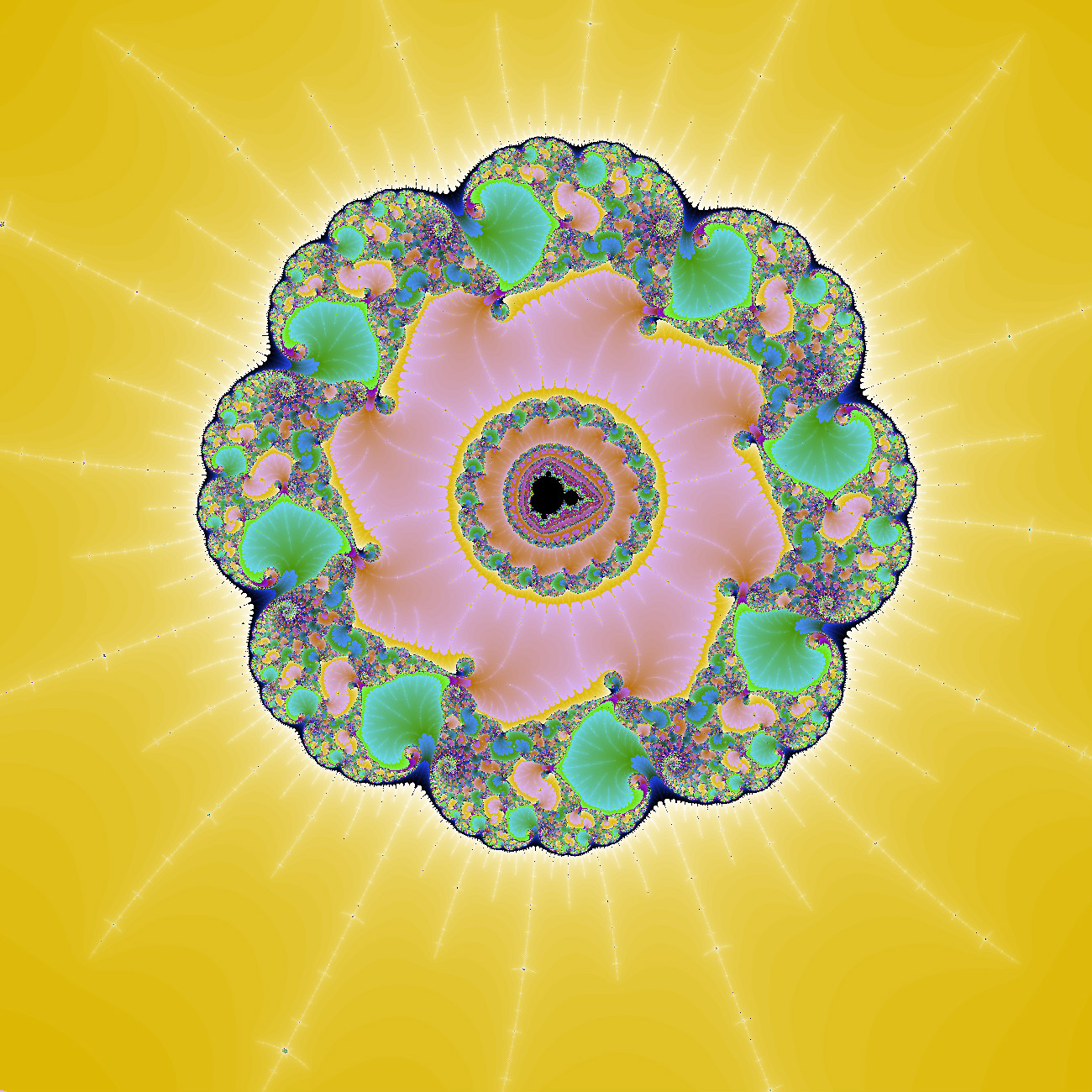

A very famous and visually stunning spontaneous order is the Mandelbrot set, the source for endless excruciatingly beautiful fractal pictures such as the one featured with this column. One of the most complex graphs known, it could not be explicitly described in a thousand years. We can only watch as shapes, curves and colorful imaginary gems emerge. How does it happen? Easy, it would seem. For each complex number C in a plane, square it and add C. Square it again and again add C. Count how many times you must do this before the result starts to take off towards infinity, and color the spot accordingly. And voilà! This is emergence. Now, of all possible things you could do with a number, most calculations will not spontaneously result in awesome graphics. Usually we just get some unwanted blur. And this is where it gets interesting, and where Mensa comes into the picture. How do we build our society so that the emergent order fosters intelligence and growth, instead of unwanted blur?

As a director of Mensa, I am interested in the mechanisms that causes one national group take off, and another group to stay stuck below the event horizon. We all have testing, and we allow just a small percentage into our club. But then? The most successful groups have more than a few things in common. Above all, they recognize the need for more than just laissez-faire social gatherings. On top of the necessary social foundation, they also seek to put the Mensa name and its pool of member resources to a good purpose. A very recent example is the ”Mensa Fonds” foundation started by Mensa The Netherlands, inspired by the American counterpart, MERF. Another is the hugely successful ”Logical Olympics” held yearly by Mensa Czech Republic – both presented at the EMAG this year.

Now, who would not want to see Mensa Foundations or Logical Olympics in all countries? Someone could be tempted to regulate all Mensas into starting foundations or olympics – but that would not work. Each country has to find the solutions that work for them, taking input from eachother. The delicate task of Mensa International remains to establish the minimum principles that will unite all countries and at the same time give enough freedom for spontaneous intelligent order to emerge.